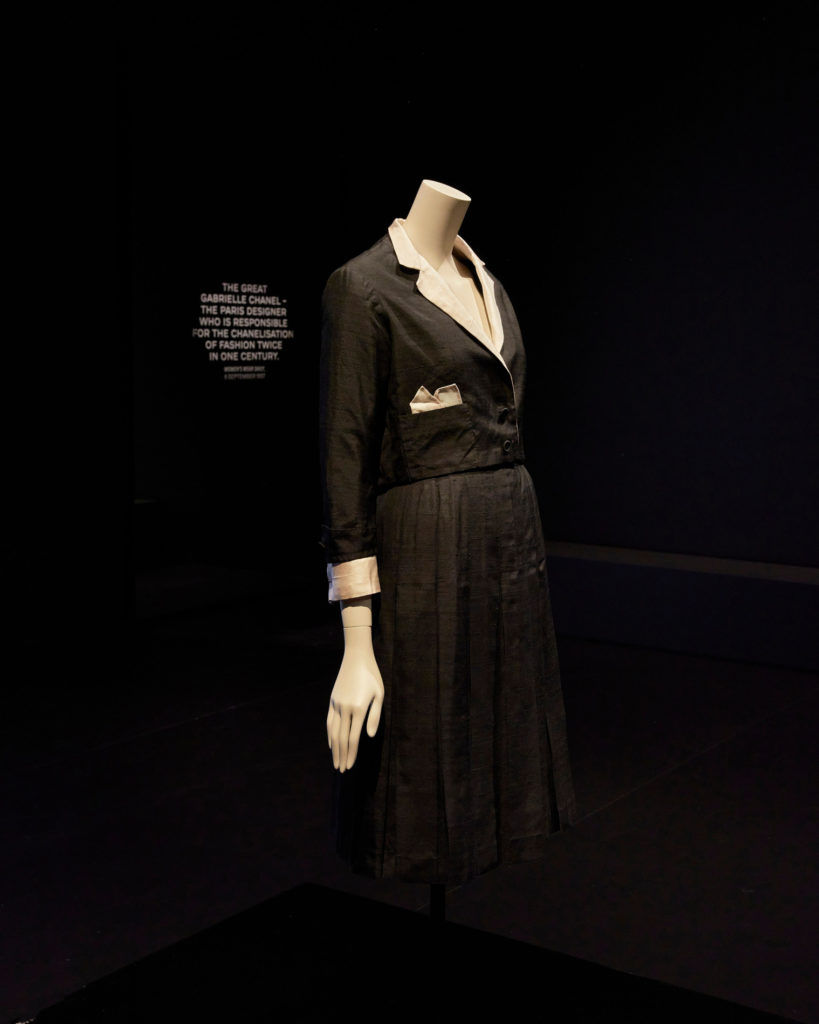

Gabrielle Chanel: Fashion Manifesto has opened in Melbourne, the first city outside of Paris to see this exclusive collection of her life’s work.

Manifesto, of Latin origin, means ‘a written statement that describes the policies, goals, and opinions of a person or group.’ Perhaps ‘code’ would be a better term for the enigmatic designer, who’s life and history has been the subject of many books on just how she emerged from childhood poverty in a convent orphanage, to become one of the most iconic, female designers the world has ever known.

code

miriam webster dictionary

/kəʊd/

noun: a system of words, letters, figures, or symbols used to represent others, especially for the purposes of secrecy.

The letters, figures and symbols used to represent what we today recognise as Chanel the brand, were all dreamt up from Gabrielle’s own vision of what it meant to be a woman in a world where fashion was largely dominated by what men dictated they should wear.

The interlocking CC logo, the austere black and white packaging and her futuristic design process codified how she wanted the world to see her, and how she wanted modern women to be seen.

“Did I have any idea of the revolution I was about to stir up in clothing? By no means. One world was ending, another was about to be born. I was in the right place; an opportunity beckoned, I took it. I had grown up with this new century: I was therefore the one to be consulted about its sartorial style. What were needed were simplicity, comfort and neatness: unwittingly, I offered all of that.”

Gabrielle chanel

One of the most affirming things about Chanel in this exhibition, is her tireless work ethic and exacting standards. Covering only her work at the house from roughly its inception to her death in 1971, you won’t see Karl Lagerfeld’s hand in any of what is on show. Rather it’s a look over the years at her earliest proffering of what a modern 20th century woman may like to wear. As Chanel recounted herself to Paul Morand in her memoirs The Allure of Chanel: ‘Why are my mannequins always the same, to such an extend that their bodies and faces are more familiar than my own? Why is it that everything that comes from my workshops from the simplest suit to the smartest dress appears to be cut by the same hand? I sculpt my pattern more than I draw it.’

The very first items you see when entering the show are a black woven straw hat dated between 1913 – 1915, and a loose blouse with a sailor collar from 1916. It’s absolutely plausible that not only were these made by Chanel herself, but that she wore and owned them. Compared to the intricate millinery that was de rigueur and corsets that were worn by women of all walks of life, these items are not just simple and functional but futuristic as well. As hard as it is to believe through a 2021 lens, women simply did not dress like this at the time.

“The women I saw at the races wore enormous loaves on their heads, constructions made of feathers and improved with fruits and plumes; but worst of all, which appalled me, their hats did not fit on their heads.”

Gabrielle Chanel, The Allure of Chanel

By Paul Morand

We can’t talk about the idea of a code however without the element of secrecy, and this is where Chanel’s murky past as a Nazi sympathiser needs to be presented. In Gabrielle Chanel: Fashion Manifesto, the focus is on her work, set against the backdrop of her breathtaking creative output. There’s a passing reference to what she did during WW II, 1939 – 1944, when the brand was shuttered, but no real mention of what she actually did, and with who for 14 years.

As Olivia Pinnock writes for Forbes, ‘It’s well documented that she had a relationship with Nazi officer Hans Günther von Dincklage during WWII and there’s plenty of evidence to suggest her collaborations didn’t stop there. Most notably, Hal Vaughan’s book Sleeping With The Enemy: Coco Chanel’s Secret War published in 2011 provides evidence that she was also involved in Nazi missions, had an agent number (F-7124) and the code name “Westminster” after her former lover, the Duke of Westminster.’

‘Chanel is not the only fashion brand with a dark past, or even present, but it stands out as a crucial one because it marries one of the most glorified fashion icons of all time and one of the most abhorrent political ideologies of all time.’

So how much of her personal life needs to be told in a retrospective about her life’s work? In terms of how the house of Chanel see it, Pinnock reflects the following:

‘A spokesperson told me: “Gabrielle Chanel was a daring pioneer, and the House of Chanel upholds and extends her extraordinary legacy. Her influence on many designers has been significant, and she continues to inspire new generations. However, her actions during World War II are the subject of discussion in many publications and biographies. The actions that some have reported in no way represent the values of Chanel today. Since that time in history, the House of Chanel has moved forward well beyond the past of its founder.”’

“Mademoiselle Chanel…was someone who traded in truth and lies with equal disdain, since ultimately everything was part of the business of the self, of herself, which was her only true raison d’être.”

Olivier saillard, essay ‘The many chanels’ gabrielle chanel: fashion manifesto

Ultimately this exhibition is worth seeing when you put into perspective the sheer amount of work Chanel got done, at a time in history when few women were able to create their own business and be financially independent from work. Through marriage or inheritance yes, but to strike out on her own (granted with the financial backing of Boy Capel to begin with) and turn a simple millinery venture into a fortune is a tale worth experiencing, in all its tweed and beaded glory.